Label STEP enforces a zero-tolerance policy on child labour, grounded in international standards, adapted to local contexts. Auditing is only one part of the work. STEP builds trust with weaving families, promoting children’s right to education, rest, and a safe, meaningful childhood.

Child labour remains a concern in many carpet-producing regions. Globally, the latest estimates from ILO and UNICEF show that 138 million children are engaged in child labour, of these 54 million in hazardous work. The latest data show a total reduction of over 22 million children since 2020, reversing an alarming spike between 2016 and 2020. Amid this, STEP’s position is clear: a child’s health, right to play and education always come first.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), child labour refers to work that deprives children of their childhood, potential, and dignity, and that is harmful to their physical and mental development. It includes work that is dangerous or interferes with schooling, whether by preventing attendance, forcing children to leave school early, or requiring children to combine long hours of work with education. The primary driver of child labour is economic necessity rather than parental neglect. Families facing financial hardship often rely on all available members, including children, to contribute. This economic pressure is the root cause behind much of the child labour observed in carpet-producing communities.

In response, STEP not only conducts audits according to the STEP Standard but also engages closely with weaving families to address these underlying challenges. The organisation supports parents in understanding the long-term benefits of education and a protected childhood, while advocating with employers, buyers, and local authorities for fairer wages and improved working and living conditions through its Weaver Empowerment Programs. These programs offer training modules on health and hygiene, lifestyle and citizenship, labour rights and responsibilities, education and the rights of women and children, as well as financial literacy, empowering workers with knowledge and skills to improve their livelihoods and secure a better future for their children. While STEP works to drive systemic change in the handmade carpet sector, its monitoring is limited to certified supply chains under its direct oversight. As such, STEP cannot speak for the wider national or global carpet industry, which remains outside the scope of its audits.

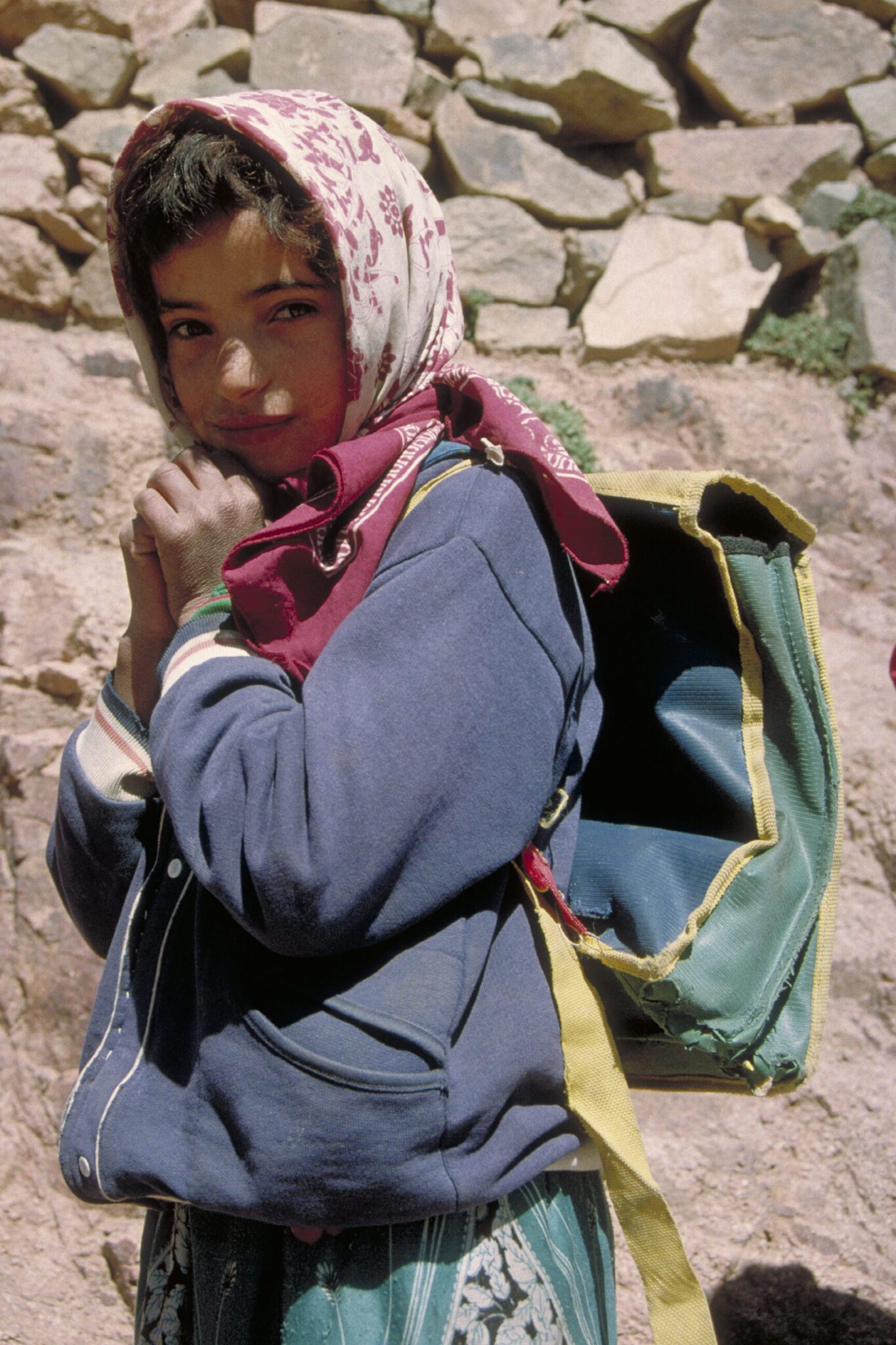

In some regions, formal schooling, particularly for girls, remains inaccessible due to systemic barriers. While STEP advocates for every child’s right to education, it also works with families to reduce risks and support children’s development in safe and meaningful ways when access to schooling is limited. Recognising the cultural importance of traditional crafts such as weaving, often passed down through generations, STEP emphasizes that any involvement by children must be voluntary, age-appropriate, and non-commercial. Such participation is only permitted within home-based production, alongside parents or family members, and must never occur in workshops or facilities outside the family home. It must also never interfere with a child’s right to education, rest, or play.

This careful, context-aware approach recognises that looms are often part of daily life and cultural identity. At the same time, it ensures that tradition does not turn into child labour. By putting education and children’s well-being first, STEP builds long-term relationships with communities, creating space for both heritage and positive change.

Upholding Standards Amid Fragility

Of all major handmade carpet-producing countries, Afghanistan presents the most complex and urgent challenge in addressing child labour. According to a 2023 report by Save the Children, more than a third (38.4%) of children surveyed in Afghanistan have been pushed into work to help their families cope with soaring levels of poverty and hunger. Amid these challenges, Afghanistan’s carpet sector remains both an economic necessity and a cultural pillar. Yet, it operates under the weight of decades of conflict, displacement, and deeply rooted inequalities.

A recent BBC article covering the relationship between Taliban schooling bans upon Afghan girls and low-paid carpet weaving highlights how the combination of economic hardship and restrictive gender policies is pushing more girls into informal, home-based weaving—significantly increasing the risk of child labour. This issue has become particularly pronounced in informal, home-based weaving, where complications—such as the need for prior notice before entering private homes—limit effective monitoring and create blind spots, while also requiring specific social skills to build trust and navigate these sensitive settings. Beyond this, limited access to formal education and activities outside the home, especially for girls, is shaped by strict socio-political restrictions and deep-rooted gender norms. As a local STEP representative notes, “Education, the alternative to child labour, is often unavailable, complicating conventional approaches. Collective dialogue is needed to find practical solutions. At STEP, we work closely with families, communities, and local stakeholders to raise awareness, reinforce compliance, and promote shared responsibility.”

“Education, the alternative to child labour, is often unavailable, complicating conventional approaches. Collective dialogue is needed to find practical solutions. At STEP, we work closely with families, communities, and local stakeholders to raise awareness, reinforce compliance, and promote shared responsibility.”

STEP representative

Above all else, the ban stands in direct conflict with international human rights standards. Label STEP condemns these restrictions and remains the only organisation that is currently systematically auditing social compliance in Afghanistan’s carpet industry. The same representative explained, “At STEP, we work closely with families, communities, and local stakeholders to raise awareness, reinforce compliance, and promote shared responsibility.” In 2024, STEP conducted 1,694 social compliance audits across key carpet-producing provinces including Kabul, Nangarhar, Herat, Bamyan, Balkh, Jawzjan, and Faryab. These audits and systems of support do more than ensure compliance—they open dialogue, raise awareness, and build trust within communities.

Navigating Child Protection and Education Barriers in Afghanistan

The complex challenges where child labour, restricted education, and home-based work overlap are best reflected in the real-life stories we encounter. In April 2025, during a routine audit in Dasht-e-Barchi, Kabul, STEP identified a 12-year-old, sixth grade student weaving carpets at home after school. She attends the highest education level currently allowed for girls, but has little discretion over how to spend her time beyond that.

STEP raised awareness with the family about the health risks of early weaving and the importance of rest and social time after school. Although the girl has stopped weaving, ongoing bans on girls’ education beyond primary school threaten progress. Monthly follow-ups monitor the child’s wellbeing. However, STEP’s ability to monitor child wellbeing is tied to supply chain access: if a weaving family stops working with a STEP-affiliated exporter, audit coverage—and thus protective oversight—may no longer be possible.This highlights the need for companies sourcing Afghan handmade carpets to maintain long-term partnerships and stay engaged to effectively protect children’s rights.

While education is not STEP’s formal mandate, it closely links to health, safety, and humane treatment standards and often arises in community work. In addition to auditing and ensuring the necessary withdrawal of children from labour in cases of non-compliance, STEP works with local stakeholders to support broader, context-sensitive efforts that reduce risks to children and foster sustainable, locally accepted change. Despite ongoing systemic barriers, STEP actively prioritises support for the most vulnerable children and families in its network.

Between Skill Transfer and Exploitation: Navigating Complex Realities

In Afghanistan, the ban on girls’ secondary education and limited opportunities outside the home present significant challenges to applying conventional child labour frameworks. Whereas, other countries producing handmade carpets, such as Nepal and India, have distinct social, political, and educational landscapes that shape how child protection measures are implemented. Nevertheless, STEP recognises that the boundary between passing down traditional skills and exploitative child labour is often difficult to define. Growing up around looms can play a meaningful role in shaping cultural identity and leading to future livelihood earning opportunities —so long as participation is voluntary, safe, and free from economic pressure.

In Nepal, the context differs significantly, as carpet weaving takes place almost exclusively in centralised workshops, rather than private homes. The legal provision that allows children to learn a craft in a family-based setting does not apply here, and children are strictly prohibited from working at the looms under any circumstances.

With this nuanced context in mind, STEP Nepal collaborated with exporters and a mobile school to provide non-formal education and vocational training for underage weavers (aged 16 to 18) who had left formal schooling. This initiative was launched after the legal working age in Nepal was raised from 16 to 18, resulting in many young workers being released from their jobs. The training was designed to help them reintegrate into formal education or find alternative pathways.

A notable example is Sabitri Nyshur, a 17-year-old from Makawanpur district. After dropping out following her eighth grade exam due to family responsibilities, she moved to Kathmandu and began weaving. When identified as an underage worker by a STEP auditor, Sabitri was taken out of weaving work. Through STEP’s support and vocational training program, she was given the opportunity to reintegrate into education. Despite caring for her sister’s children and managing the household, she remained motivated, pursued non-formal education, passed a level test, and successfully completed the grade eight exam.

“I didn’t know that children were restricted from working in the carpet sector. I was more focused on earning for my family than on studying. With the support of Label STEP, I joined a non-formal class held at the workplace. Recently, I took the Grade 8 exam and am now waiting for the results. This opportunity inspired me, and I am very motivated to continue my education.”

In addition to these efforts, in Nepal STEP is collaborating with municipal and ward governments to support monitoring activities and advance child labour-free declarations. This collaboration includes supplier sensitization, weaver orientation sessions, monitoring visits, and rescue and remediation efforts — all aimed at ensuring that specific wards are free from child labour or workers under 18. Local governments lead the initiative, working with NGOs and private sector stakeholders who provide technical and financial support.

Similarly, in India, evening classes known as “midnight schools” were introduced over a decade ago to help reintegrate children working in home-based or informal loom settings back into education. These schools were created in response to the realities faced by many weaving families, where children often contributed to the household income through carpet weaving and lacked access to formal schooling. The “midnight schools”offered daily two-hour classes in reading, writing, maths, and practical skills, as well as activities such as singing and dancing to foster creativity and confidence.

The programme also engaged families and the wider community. Many mothers took part in separate literacy classes, and as families witnessed the educational progress of their children, more parents were motivated to enrol their younger children in school. Over time, the schools helped shift attitudes towards education while strengthening community cohesion and opening up broader opportunities for the families involved. These examples reflect STEP’s deep commitment to adapting child protection strategies to the complexities of local contexts.

Staying Matters: Engagement as Protection

Cultural and political contexts are constantly evolving, and so too must the handmade carpet industry’s response to how it monitors and combats key issues like child labour. In Afghanistan, for example, disengagement might seem principled from afar, but on the ground, it would mean abandoning families who depend on weaving for survival and leaving children without advocates. For women, who compose the majority of Afghanistan’s weavers, the loom is often one of the last spaces for income and creative expression. As women’s rights are increasingly dismantled, preserving these roles takes on urgent importance.

STEP’s ongoing presence is a deliberate choice to stand with the people keeping the sector alive. From supporting access to education and health services to helping producers shift toward higher-value custom orders allowing for better wages, STEP’s work reinforces the dignity, well-being, and self-reliance of artisan communities without legitimising those in power but by protecting those who endure under it.

A Shared Responsibility

In 2024, STEP conducted more than 2,700 social compliance audits, covering over 13,000 artisans across all operational regions, with child labour assessed as a key criterion in every audit. Across all regions where STEP operates, there has been a general decline in the number of child labour cases within certified supply chains. This trend reflects multiple factors: growing awareness among exporters and weaving families, long-term community engagement, better economic conditions in some regions, and increased access to schooling. In many places, child weaving is no longer a sustainable option as household incomes rise and educational opportunities increase. Another emerging trend is an aging artisan workforce, as younger generations pursue other career paths.

Eliminating child labour in the handmade carpet sector requires more than policies; it demands consistent monitoring, local engagement, and cooperation across the supply chain—even more under policies such as those of Afghanistan. STEP combines rigorous audits with community dialogue and support for families to reduce risk and drive long-term change. While STEP’s work offers valuable insight into certified supply chains, it does not represent the sector as a whole. Broader, lasting change will require coordinated action by governments, NGOs, producers, buyers, and consumers. Buying rugs from fair-trade certified brands is one way consumers can contribute to safer, more transparent working conditions.

No matter where artisan traditions and child protection systems face threats, STEP’s continued presence provides structure, accountability, and a pathway to safer, more sustainable production. Combatting child labour is an ongoing effort, one that continuously adapts to changing social, economic, and political realities, ensuring support remains effective and relevant on the ground.

Visit the STEP Standard “Prohibition of Child Labour” for more information.